One of at least 18 Odyssey mosaics reported stolen from northeastern Syria in early 2013. This is a detail of Odysseus tied to his mast, resisting the sirens. Despite reports, conflicting information originally places this mosaic in Tunisia, not Syria. Image Source: Past Horizons.

Since 2011, reports have circulated that Syria's classical heritage is being ruined or plundered by the conflict in that country. When war began, there were some 78 formal archaeological digs in the country. Then the conflict between the population and the government, followed by the Islamic State, led to an obliteration of Syria's precious past. Islamic State militants, like the Taliban, abhor graven images, although they are still willing to sell the stolen artifacts which they don't destroy. They are not alone on that black market.

Full mosaic: Odysseus and the Sirens at the Bardo Museum in Tunis, Tunisia (2nd century AD). Image Source: Wiki.

On 2 September 2014, the New York Times reported that the Islamic State has set up a nasty sideline selling Syrian archaeological artifacts:

We have recently returned from southern Turkey, where we were training Syrian activists and museum staff preservationists to document and protect their country’s cultural heritage. That heritage includes remains from the ancient Mesopotamian, Assyrian, Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine and Islamic periods, along with some of the earliest examples of writing and some of the best examples of Hellenistic, Roman and Christian mosaics.

In extensive conversations with those working and living in areas currently under ISIS control, we learned that ISIS is indeed involved in the illicit antiquities trade, but in a way that is more complex and insidious than we expected. ...

ISIS permits local inhabitants to dig at these sites in exchange for a percentage of the monetary value of any finds.

The group’s rationale for this levy is the Islamic khums tax, according to which Muslims are required to pay the state treasury a percentage of the value of any goods or treasure recovered from the ground. ISIS claims to be the legitimate recipient of such proceeds.

The amount levied for the khums varies by region and the type of object recovered. In ISIS-controlled areas at the periphery of Aleppo Province in Syria, the khums is 20 percent. In the Raqqa region, the levy can reach up to 50 percent or even higher if the finds are from the Islamic period (beginning in the early-to-mid-seventh century) or made of precious metals like gold.

The scale of looting varies considerably under this system, and much is left to the discretion of local ISIS leaders. For a few areas, such as the ancient sites along the Euphrates River, ISIS leaders have encouraged digging by semiprofessional field crews. These teams are often from Iraq and are applying and profiting from their experience looting ancient sites there. They operate with a “license” from ISIS, and an ISIS representative is assigned to oversee their work to ensure the proper use of heavy machinery and to verify accurate payment of the khums.

To control history, especially to squander or erase it, is to control the future. There are some 10,000 archaeological sites scattered across the country. All are now vulnerable.In addition to the looting, ISIS seems to be encouraging the clandestine export of archaeological finds, which is primarily centered on the border crossing from Syria into Turkey near Tel Abyad, an ISIS stronghold. There is reason to suspect that ISIS has approved and encourages the transborder antiquities trade.

Aramaic gold-plated bronze statue stolen from Hama Museum (stolen 14 July 2011). Photo: Dick Ossemann via University of Copenhagen.

Trouble began with conflict: the University of Copenhagen noted that an Aramaic gold-plated bronze statue had been stolen from the Hama Museum in July 2011. Interpol sounded an alarm over mosaics in the city of Hama and the ancient city of Afamya (Apamea, Apamya, Efamya, Epamea) in May 2012. Losses in 2012 included mosaics stolen from the ruins of Apamea, shown below. Apamea was a "treasure city and [horse] stud-depot of the Seleucid kings, and was the capital of Apamene."

Founded by one of Alexander the Great's generals around 300 BCE, Apamea was once a grand metropolis of half a million people, along with tens of thousands of horses and 500 elephants. The Romans conquered it and incorporated it into their territories in 64 BCE. It had one of the largest theatres in the Roman world, with seating for 40,000 people, and an incredible colonnaded main avenue. Travel writer Wandering Earl visited the site in October 2010, before the conflict:

By February 2014, Haaretz reported that Apamea had been "completely destroyed" by illegal digging.This place blew me away. To see an ancient Roman avenue, lined with hundreds of columns stretching for such a great distance and set on a plateau overlooking the Ghab valley, was quite a remarkable sight. All I did was walk up and down this avenue a couple of times but I had never been to an ancient Roman city where it was so easy to actually envision what life was like back in those days. Not only were there hundreds of mostly intact columns, but there were archways, facades, temples, bathhouses and other structures that were quite well-preserved. I could almost hear the horse[s] and chariots traveling along this main road as well as the philosophers offering their wisdom to all those who passed them by.

Nearby sites include Krak des Chevaliers (a Crusaders' castle), and Serjilla, both of which have suffered looting and destruction. See my earlier post on Krak des Chevaliers here, when it was shelled by the Syrian army. Syria's whole northwestern region is dappled with cities and towns which prospered from classical times to the middle ages. Wiki lists Syrian heritage sites damaged during the civil war here. UNESCO links progressively reveal the country's growing tragedy:

- Six new sites inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List Jun 27, 2011

- Director-General of UNESCO appeals for protection of Syria’s cultural heritage Mar 30, 2012

- UNESCO Director-General deplores the increasing threats and possible damage to the Umayyad Mosque in Aleppo, Syria Oct 11, 2012

- Director-General of UNESCO reiterates her appeal for the protection of Syria’s cultural heritage Jun 2, 2013

- Syria’s Six World Heritage sites placed on List of World Heritage in Danger Jun 20, 2013

- UNESCO Director-General deplores the escalation of violence and the damage to World Heritage in Syria Jul 16, 2013

- “Stop the destruction!” urges UNESCO Director-General Aug 30, 2013

- Emergency Red List of Syrian Antiquities at Risk is launched in New York Sep 30, 2013

- UNESCO to create an Observatory for the Safeguarding of Syria’s Cultural Heritage May 28, 2014

- UNESCO strengthens action to safeguard cultural heritage under attack Aug 12, 2014

Apamean mosaics, looted from Hama (2012). Image Source: Lootbusters.

Apamean mosaics at risk, possibly destroyed. Image Source: Dick Osseman via Lootbusters.

More mosaics at risk, likely destroyed, Hama Museum. Image Source: Dick Osseman via Lootbusters.

In February 2013, Syria's Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums promised at an international conference that Syria's treasures had been moved and secured:

In February 2013, a UNESCO workshop dedicated to illegal trafficking in Syria took place in Jordan and was attended by academic and government organizations from various countries. During the workshop, officials from the DGAM stated: ‘We emptied Syria's museums; they are in effect empty halls, with the exception of large pieces that are difficult to move’. Officials also confirmed that tens of thousands of artifacts had been transferred to private stores to protect them from looting and avoid a repeat of the events in Baghdad after the 2003 invasion. The DGAM report of February 2013 reconfirms that all archaeological artifacts and historic art has been removed to safe and secure places, and they have increased the number of guards and installed burglar alarms in some museums and historic buildings.

"These mosaics were stolen during illegal excavations on archaeological sites in the war-torn country’s northeast," Lubana Mushaweh said in an interview published on Sunday [3 March 2013] by the government daily Tishreen. "We have been informed that these mosaics are now on the Syrian-Lebanese border," she said without elaborating.

"Under the cover of revolutionaries, gangsters penetrate Syria – mostly from Jordan – and perpetrate crime. Western media present them as 'freedom fighters' and transform their criminal activities as heroic acts." [F]ierce fighting and deteriorating security have left the country’s extraordinary archaeological heritage susceptible to damage and prey to a rising number of looters.

Ebla was the seat of one of Syria's earliest kingdoms. It was there that writing was first developed in the cuneiform script, 3000 years before Christ. By September 2013, an archaeological student blog at Michigan State University commented:"Three of the most important archae[o]logical sites in Syria are Afamya, Ebla, and Mari." ... "Every time a tire moves in its circle, a piece of thousands of years of history will rotate on the thin roads and alleys of Syria ... . And every time you open the window, you smell the perfume of Zenobia, Balkis, and Ishtar, feeling their presence as we look at the ruins that still exist in different shapes, sizes, and colors, confirming the truthfulness of their great era."

Because of Ebla’s location on the top of a mound, armies can see other military members (friend or foe) from far away, land or sky. Other sites originally built millennia ago for militaristic use are now inhabited again for the same purpose as well, but now there’s a new danger in all of the warfare, and that’s the archaeological damage.

At Ebla, a group of rebels that call themselves The Arrows of the Right stand guard with radios to report in about attack jets. They’ve also tried to protect the site, preventing it from being razed by a bulldozer.

However, as a gravesite, Ebla has been looted for any potential riches that might be buried with its bodies, which have been thrown carelessly away. It is a stark contrast between the meticulous excavation by the archaeologists that had only sifted through a small portion of the site, and children digging in the dirt for artifacts to sell.In April 2013, the New York Times reported that Ebla had been seized as a strategic lookout point and its ruins are being devastated. Two looters were killed excavating at Ebla with a bulldozer when the roof of the cave they were in collapsed. Artifacts stolen from Ebla have turned up in Jordan. In June 2014, Cradle of Civilization blog reacted with alarm:

10,000 years ago, the first crops and cattle were domesticated: the subsequent settlement gave rise to some of the first city states, such as Armi, later known as Aleppo, Ebla and Mari. ... As the people of Syria continue to endure incalculable human suffering and loss, their country’s rich tapestry of cultural heritage is being ripped to shreds. World Heritage sites have suffered considerable and sometimes irreversible damage. Four of them are being used for military purposes or have been transformed into battlefields: Palmyra; the Crac des Chevaliers; the Saint Simeon Church in the Ancient villages of Northern Syria; and Aleppo, including the Aleppo Citadel. ...

All layers of Syrian culture are now under attack – including pre-Christian, Christian and Muslim. ... Damage to the site of Ebla (Tell Mardikh, near Idlib) caused by illegal excavations and vandalization of the site carried out by locals, fighters and agents of organized trafficking in antiquities. The destruction of such precious heritage gravely affects the identity and history of the Syrian people and all humanity, damaging the foundations of society for many years to come.

Statue from Mari: "The ... statue is of the Iku-Shamagan, King of Mari. It dates to about

2650 B.C. and is from the temple of Ishtar in Mari. The statue is about

47 inches high and was displayed in the Damascus Museum in 2002 when I [Ferrell Jenkins]

made this photograph." Image Source: Ferrell's Travel Blog.

Mari was an ancient Sumerian and Amorite city on the western bank of the Euphrates river, inhabited since the 5th millennium BCE. Let me repeat that: inhabited since the 5th millennium BCE. In February 2014, Crikey reported that rebels have been excavating the area with jackhammers and bulldozers:

The buried Bronze Age city of Mari on the Euphrates River in eastern Syria has been giving up its secrets to French and Syrian archaeologists since its discovery in 1933. But the Syrian civil war threatens the precious artifacts therein.

Forty-two excavation campaigns over almost 80 years have unearthed a 300-room palace, brilliantly coloured frescoes and more than 25,000 clay tablets written in cuneiform script, one of the earliest writing systems.

When fighting between the Syrian army and rebels brought work to an abrupt end in 2011 less than half the 60-hectare site had been uncovered. An unknown number of cultural layers lie below ground. Now an armed gang of treasure hunters equipped with bulldozers has supplanted archaeologists’ painstaking efforts with trowels, brushes and soil sifters.

Mari is one of hundreds of Syrian historical sites under assault from international gangs of thieves “organised like the Mafia”, said Minister for Culture Dr Loubana Moushaweh when I interviewed her in Damascus recently.

Interpol has issued an alert for stolen Syrian antiquities and helped recover Roman mosaics trafficked into Turkey. More promisingly, the national museum network is largely secure, with almost all holdings documented electronically, Moushaweh says. This contrasts with neighbouring Iraq’s museums, which were left unprotected to suffer widespread looting following the US invasion in 2003.

Some of Syria’s six World Heritage historical areas have suffered serious war damage, but Moushaweh suspects the greatest losses will turn out to be the destruction of historical evidence and hitherto undiscovered riches as thieves dig for gold, jewelry, statues and mosaics at unguarded archaeological sites. Most of Syria’s archaeologically rich regions are in rebel hands.

A few kilometres from Mari is the walled Hellenistic and Roman city of Europos-Dura. The Syrian government submitted both of these Euphrates Valley sites for World Heritage listing in 2011, but they soon fell under the control of feuding rebel bands.

At Europos-Dura — explored by French, American and Syrian archaeologists since the 1920s — about 300 gang members are using heavy machinery to carry out “fierce excavation” that has destroyed 80% of the 56-hectare site with holes up to three metres deep, according to a recent report by Syria’s general director of antiquities and museums, Professor Maamoun Abdulkarim. Illegal digging sped up in September last year [2013] after someone found a gold bracelet at the site.

From the Independent, also in February 2014:But Moushaweh, a former Damascus University dean appointed to head the ministry in 2012, says Mari is the site of greatest concern because use of earth-moving equipment had caused “irreparable damage”. Mari is thought to have been inhabited since the fifth millennium BC. Moushaweh says the gang has settled into the archaeological mission residence and visitor centre and is working off satellite pictures and using metal detectors. ... Aerial photographs show hundreds of ancient cities and graveyards “as cratered as the surface of the moon” following illegal digging, reported Erin Thompson, a US expert on art crime.

In March 2014, the NYT interviewed French archaeologist Jean-Claude Margueron, who excavated Mari for many years and spoke of his pain:Theft of antiquities is particularly bad in the far east of Syria at Mari where an armed gang numbering 500 has taken over the site. An official report says that the looters have been focusing on “the Royal Palace, the southern gate, the public baths, Temple of Ishtar, the Temple of Dagan and the temple of the Goddess of Spring”.

Culpability for this destruction rests with government forces, rebels and the Islamic State. The government issued a report on damage in January 2014. As the conflict has worsened, so has the finger-pointing over who has done what. The government of Syria denies all participation in the plunder, but government critics say that Assad's troops have joined in it. The sale of artifacts funds arms deals. A mafia organization based in Iraq, Lebanon and Turkey has hired hundreds of people to strip sites. The list goes on: Homs. Hama. Old Damascus. Palmyra (go here to see bulldozers excavating Palmyra; Hat tip: APSA). Aleppo.“Mari was one of the first urban civilizations where man lived[.] ... If you pillage Mari, you destroy Mari. These are irremediable losses.”

Image Source: The Independent.

Meanwhile, the UN has pleaded uselessly for the destruction to stop, culminating with a March 2014 statement from Ban Ki-moon:

We call on all parties to halt immediately all destruction of Syrian heritage, and to save Syria’s rich social mosaic and cultural heritage by protecting its World Heritage Sites, in line with UN Security Council Resolution 2139, adopted on 22 January 2014.

We condemn the use of cultural sites for military purposes and call on all parties to the conflict to uphold international obligations, notably the 1954 Hague Convention for the protection of cultural property in the event of Armed Conflict and customary international humanitarian law.

We appeal to all countries and professional bodies involved in customs, trade and the art market, as well as individuals and tourists, to be on alert for stolen Syrian artifacts, to verify the origin of cultural property that might be illegally imported, exported and/or offered for sale, and to adhere to the UNESCO 1970 Convention on illicit trafficking of cultural property.

UN appeal to safeguard Syria's cultural heritage, from the Director-General of UNESCO, Irina Bokova (30 August 2013). Video Source: UNESCO via Youtube.

Pre-Islamic mosaics from Raqqa, destroyed by the Islamic State. Images Source: Patrick Cockburn/The Independent.

In Raqqa, ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria), the al-Qaeda-affiliated group which aims to establish an Islamic state across Iraq, Syria and the Levant, has imposed strict Islamic law. There, several pre-Islamic mosaics have been destroyed to purge idolatry. The Independent reports:

Islamic fundamentalists in Syria have started to destroy archaeological treasures such as Byzantine mosaics and Greek and Roman statues because their portrayal of human beings is contrary to their religious beliefs. The systematic destruction of antiquities may be the worst disaster to ancient monuments since the Taliban in Afghanistan dynamited the giant statues of Buddha at Bamiyan in 2001 for similar ideological reasons.

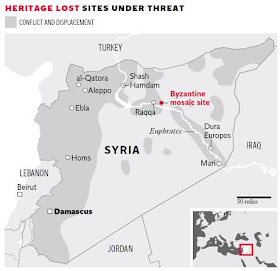

In mid-January [2014] the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (Isis), an al-Qa’ida-type movement controlling much of north-east Syria, blew up and destroyed a sixth-century Byzantine mosaic near the city of Raqqa on the Euphrates. The official head of antiquities for Raqqa province, who has fled to Damascus and does not want his name published, told The Independent: “It happened between 12 and 15 days ago. A Turkish businessman had come to Raqqa to try to buy the mosaic. This alerted them [Isis] to its existence and they came and blew it up. It is completely lost.”

Other sites destroyed by Islamic fundamentalists include the reliefs carved at the Shash Hamdan, a Roman cemetery in Aleppo province. Also in the Aleppo countryside, statues carved out of the sides of a valley at al-Qatora have been deliberately targeted by gunfire and smashed into fragments.

Professor Maamoun Abdulkarim, general director of antiquities and museums at the Ministry of Culture in Damascus, says that extreme Islamic iconoclasm puts many antiquities at risk. An expert on the Roman and early Christian periods in Syria, he says: “I am sure that if the crisis continues in Syria we shall have the destruction of all the crosses from the early Christian world, mosaics with mythological figures and thousands of Greek and Roman statues.”

Of the mosaic at Raqqa, discovered in 2007, he says: “It is really important because it was undamaged and is from the Byzantine period but employs Roman techniques.”

Syria has far more surviving archaeological sites and ancient monuments than almost any country in the world. These range from the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus with its magnificent eighth-century mosaics to the Bronze Age Ebla in Idlib province in north-west Syria, which flourished in the third and second millennia BC and where 20,000 cuneiform tablets were discovered. In eastern Syria on the upper Euphrates are the remains of the Dura-Europos, a Hellenistic city called “the Pompeii of the Syrian desert” where frescoes were found in an early synagogue. Not far away, close to the border with Iraq, are the remains of Mari, which has a unique example of a third-millennium BC royal palace.

Unfortunately, many of the most famous ancient sites in Syria are now held by the fundamentalist Islamic opposition and are thereby in danger. Professor Abdulkarim says that it is not just Isis but “Jabhat al-Nusra [the official affiliate of al-Qa’ida] and the other fundamentalists who are pretty much the same”.

"This undated file image posted on a militant website on Tuesday, Jan.

14, 2014 shows fighters from the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS)

marching in Raqqa, Syria." Image Source: AP /militant website via Asharq al-Awsat.

"According to a report from the website www.apsa2011.com, the Islamic State ... has destroyed Assyrian statues and artifacts believed to be 3000 years old." (May 2014) Images Source: AINA.

Wreckage at the Aleppo Museum (February 2014). Image Source: RT via Syria News.

The sandbagged and protected entry to the Aleppo National Museum (April 2014).

Image Source: Sam Dagher/The Wall Street Journal.

An ancient stone lion is covered with sandbags at the Aleppo National Museum (April 2014). Image Source: Sam Dagher/The Wall Street Journal.

By 2013 and 2014, devastation reached Damascus and Aleppo:

The old city is a unique collection of ancient temples, mosques, churches, bustling souks, caravansaries, traditional homes and narrow alleyways and streets spanning an area of about 1,000 acres. Nearly 240 structures have been classified as historic buildings by the Old City Directorate.

Before the war a German-funded urban renewal plan helped upgrade the infrastructure and many traditional homes, which had been crumbling at the time, while the Aga Khan Development Network renovated the medieval citadel that anchors the old city. Tourists flocked in droves, and people like Faisal Kudsi, a Syrian-born British banker who converted two traditional homes into opulent boutique hotels, invested.

"Today all you see are occasional fighters dashing in the alleyways and a terrifying silence sliced by gunfire from time to time," said the man who surveyed the damage recently.

Video Source: WSJ.

The Conversation offers a final word:

As the collective history of Islam, Christianity and Judaism is erased, Syrians are left with an abominable tabula rasa. Anything may be written on that blank slate. Those who write on that slate by perpetrating these acts are not the creators - as they claim to be - of new societies and civilizations. They are the agents of anti-civilization.It is worth remembering that many of the endangered archaeological sites and artefacts we treasure are the result of looting and destruction perpetrated by the very civilisations whose histories we seek to preserve and understand.

No comments:

Post a Comment