W. B. Yeats by John Singer Sargent.

Today is the sesquicentennial 150th anniversary of the birth of the great Irish poet, William Butler Yeats (1865-1939). Many modern poets have captured the spirit of our times. But Yeats stands out as a Romantic Modernist whose work most clearly described the great transition of our times, from one age to another. In his works, he depicted periods of time as sharply-dermarcated sections of human experience during which certain symbolic, spiritual, moral, occult or magical ideas gained total dominance. Thus the passage of time and the turn of ages was imagined by the poet as a violent, ongoing battle between contending philosophies and ways of being. Yeats equated the passage of time with millennia-long developments in collective human psychology. To understand how and why Yeats depicted the current Millennial transition so rarely and perfectly, we need to travel backward through his life, from the end of his days when his visions of the future were most pronounced, to the influences of his early childhood (Thanks to -C.).

The Transition to a New Age

Yeats's poems are defined by the tension between opposites, stresses between states of being, between ideal and real, and fixate on antagonisms between cultures. Yeats was the offspring of parents who did not see eye-to-eye: a bright, unconventional artist father, John Butler Yeats (1839-1922), and a depressive Protestant mother, Susan (1841-1900), from a merchant branch of the aristocratic Pollexfen family. His was a divided self, hammered together by imagination; Michael Braziller and Eamon Grennan confirm he spent incredible creative efforts trying to reconcile vastly different energies which were assaults on the self. He grew up splitting his time between London where his father had moved them, and his mother's family's base in the traditional and wild world in County Sligo, Ireland. The BBC commemoration of Yeats's 150th birthday anniversary includes an essay on these tensions, here. The essayist, Fintan O'Toole, concludes that you cannot understand Yeats without grasping his need to balance opposites - or to find some universal transcendence above them. The poet always rejected the simple answer, demanded complexity, and yet yearned paradoxically for unity above all. The National Library of Ireland has an online Yeats exhibition (here) which shows some of these complexities.

To Yeats, it must have seemed as though the small oppositions of his young life magnified and grew, increasingly projected across the landscape of humanity over the course of time. First, there was the decline of the Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. This grew into the Irish revolt against British rule in 1916, followed by the 1917 establishment of the Irish Republican Army and the Irish War of Independence from 1919 to 1921. There were the Russian Revolutions of 1905 and 1917. And there was the Great War from 1914 to 1918. During his lifetime, the entire world was consumed by momentous conflict! You can see his struggle to overcome that conflict artistically in the poem, An Irish Airman Foresees his Death (1918).

An Irish Airman Foresees His Death (1918) By W. B. Yeats. Read by Lemn Sissay (2014). Video Source: Youtube.

An analysis of An Irish Airman Foresees His Death by Hazel Dempster (2013). Video Source: Youtube.

Out of the psychological tension between opposing forces, Yeats foresaw the birth of a new era. His most famous poem is The Second Coming, written one year after An Irish Airman Foresees His Death. It describes how these conflicts would lead us into a new age after a psychological break and turnover, where old mythical symbols would revive and reverse the meanings of commonly-held values. Yeats arguably did not intend these symbols to be taken literally, in terms of man-beast monsters actually walking around on the face of the earth. Rather, he poetically explained that a new age would arrive in the wake of a deadly psychological turn.

"The falcon cannot hear the falconer." Savaoph God the Father (1885-1896) by Victor Mikhailovich Vasnetsov (1848 – 1926). Image Source: pinterest.

In this period of flux, people would start to think like beasts and thereby become monsters. They might imagine they were enacting a policy of self-help, survival, and victory over their enemies. They might think they were acting as saviours or becoming small Messiahs in their societies. In fact, by playing god and succumbing to the grim narcissistic fantasy of messianic power, every single eschatological believer would become a little Antichrist, reborn in delusion as half-man, half-animal, because he or she had excused him- or herself to do whatever he wanted, without the spiritual restraint associated with the Christian human-divine.

THE SECOND COMING (1919-1920)

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: a waste of desert sand;

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Wind shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

Yeats considered that the new era could not be born without falling into a huge conflict with a spiritual ancestral enemy across time and space. Across time, his man-beast prophecy repeated in his graphic poem, Leda and the Swan (1924) which implied that the Trojan War emerged from ancient abuse of power and passion, starting with a swan raping Leda, Queen of Sparta. This act of bestiality and royal infidelity, which occasioned the conception of the illegitimate princess Helen of Troy, was 'okay' because the swan was actually the god Zeus in disguise.Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: a waste of desert sand;

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Wind shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

With The Second Coming, Yeats left no room for that kind of ambivalence. The lust for power had gone too far. The Antichrist Messiah was Ancient Egypt's riddler Sphinx reborn. It would shape the spiritual values of the post-Christian era or gyre of time. The creature would revive through men mating psychologically with beasts - or twisting nature physically to create man-beast hybrids - in order to gain power. This abominable choice would revive the pre-Christian time, when people worshiped beasts and nature, and confused their identities and abilities with them. That confusion inevitably led, Yeats argued, to conflagration and great wars, because humans would exchange the best of themselves for the worst of themselves. That time, he said, had come around again.

Across space, Yeats invoked a spiritual struggle bigger even than the internal western conflict that was World War I. The Second Coming's anti-Christian Messiah embodied a story of east-versus-west. This poem showed Yeats at his most uninhibited and powerful. Read it today, and his voice still booms across generations. Beyond the limited wars of politics, he believed spiritual wars transpired across much longer timelines. The Second Coming marked the expansion of Yeats's awareness to the temporal vastness of the human psychological landscape, journey and struggle.

Ozymandias (1817) by Percy Bysshe Shelley. Read in 2013 by Bryan Cranston, star of Breaking Bad (2008-2013). Video Source: Youtube.

Shelley's poem depicted the east in a style that Edward Said would call classic, stereotyped orientalism. This was a static, ruined east, an exotic object of fascination, even when blasted by time into sand. The poem contrasted the broken statue of Ozymandius (Ramses II) with a fictional traveler's account of it, from which Shelley spun his poem. Pitted against dynamic western knowledge, information and creation (whether in a biblical sense, or in secular art), the crumbled monolith and the tyrant it represented had lost all. Shelley's western poem implicitly triumphed over Ancient Egypt's broken monument to eastern authoritarianism.

The Second Coming (1919) by W. B. Yeats. Video Source: Youtube.

By the time Yeats wrote his poem, one hundred years on, everything had changed. Shelley's unquestioning western cultural triumph and east-west dichotomy were gone. The later poem predicted that time would turn over and the Christian era come to a horrific end. Western knowledge would run amok. The Second Coming was meant to be one part incantation, one part revelation. It is almost as though its rhythmic recitation could magically entangle the reader in the very unfolding catastrophe which Yeats described. This time, there would be no crumbled, inert statue. The ruined monument to eastern power would revive. This time, the Sphinx would come alive, move, shake off the sands of time, and slouch to Bethlehem to be reborn.

The east-west symbol was shorthand for internal religious-psychological states of being. The poem predicted: Jesus will not return in a moment of Christian triumph. Yeats foretold: this Second Coming will not be the messianic return that Christians expect. It will be the return that Christians deserve. And not just Christians will suffer: all humans will reap in the new age what they sowed in the old one. In lines borrowed from Shelley's Prometheus Unbound, Yeats promised that no one will escape, be they "the best" or "the worst": everyone will pay. Conventional morality and religion will be negated, and the fabric of civilization will be tested as individuals fend for themselves. Time is larger than any god.

Belief in Harold Camping's evangelical prediction of the Second Coming focused on 2011. Image Source: Web Pro News.

Jump forward another hundred years, and we find today's millenarians, from Christian believers to ISIS, believing that apocalypse, Rapture, Revelation, Armageddon, Resurrection, Second Coming, and Judgement Day (Yawm ad-Dīn) are at hand. Believers view this tumultuous disaster, revolution, and overturning of reality as a sort of spiritual Superbowl or World Cup, at the end of which we will find out whose world view was right. Because everyone these days is too literal-minded, the symbolic disaster is taken to be a real, forthcoming event. Extreme jihadists are among the most glaring examples who are consciously, willfully turning an apocalyptic Caliphate into a reality. Some would argue that the same desperate ideas are exploited in disaster capitalism.

Whether you are an Eschatological Marxist or a neo-Mayan, the one thing you don't want your apocalypse to be is a great big non-event. Therefore, if you are a believer, you have to show you really mean business to start the ball rolling. Taking religious prophecies literally not only shows your belief system is authentic, serious stuff; it serves a real world purpose. It justifies extreme thoughts and actions. Emergencies permit people to drop their inhibitions and to commit crimes or create chaos in the name of the new higher order they think they are building. They believe they are literally following the steps to bring surreal fantasy into real existence, to give religious prophecy a tangible form. This is abominable. The Atlantic describes the ISIS agenda:

More civilized eschatologists, such as the Sword of God cult, simply bump the date of the Second Coming forward (in this case, to 1 January 2017). They thereby gain the utility of chattering about the end of the world, and can profit from it, without having to do anything too drastic.Denying the holiness of the Koran or the prophecies of Muhammad is straightforward apostasy. But Zarqawi [who died in 2006] and the state he spawned take the position that many other acts can remove a Muslim from Islam. ... Being a Shiite, as most Iraqi Arabs are, meets the standard ... because the Islamic State regards Shiism as innovation, and to innovate on the Koran is to deny its initial perfection. (The Islamic State claims that common Shiite practices, such as worship at the graves of imams and public self-flagellation, have no basis in the Koran or in the example of the Prophet.) That means roughly 200 million Shia are marked for death. So too are the heads of state of every Muslim country, who have elevated man-made law above Sharia by running for office or enforcing laws not made by God.

Following takfiri doctrine, the Islamic State is committed to purifying the world by killing vast numbers of people. The lack of objective reporting from its territory makes the true extent of the slaughter unknowable, but social-media posts from the region suggest that individual executions happen more or less continually, and mass executions every few weeks. Muslim “apostates” are the most common victims. Exempted from automatic execution, it appears, are Christians who do not resist their new government. Baghdadi permits them to live, as long as they pay a special tax, known as the jizya, and acknowledge their subjugation. The Koranic authority for this practice is not in dispute.

Image Source: AP via Daily Mail.

Human beings love doomsday. The predicted end of the world and the birth of a new order are one of the most enduring and popular stories across all times and cultures. Fear of impending apocalypse is really fear of existence of the present; the shock experienced by change and upheaval; a yearning for a secure (but troubled) past which can no longer save us, or for a big future resolution to clamp down on chaos. For as long as we can trace records back, people have been predicting total destruction as a way of coping with a tumultuous present. In that eternal fixation on cataclysm lies a clue to Yeats's real purpose.

Occult Gyres of Time

Why would a western poet predict the defeat of the west? Is that in fact what Yeats was doing in The Second Coming? It is easy to assume that, but Yeats's interest in the occult hints that his poems are real world incantations - actual magical spells. Some of his poems are meant to be sung, and when anyone recites them, the reader helps cast an ever-growing spell of Yeats's devising. His poems were conceived as real-world applications of spirituality and symbolism, in a way that might resonate with a Postmodern Druid like Alan Moore. This means Yeats's poems demand rereading, not just for their creative mastery, but for his magical intentions. Do these spells make poetic symbols into emblems of human consciousness of the natural world? Were they made to do this in order to counteract the literal-minded eschatologists, like those of ISIS, who try to turn symbols into tools of everyday reality?

In George's Ghosts, Yeats's biographer Brenda Maddox comments that members of the Anglo-Irish Ascendancy became obsessed with the occult as they declined (Maddox, George's Ghosts, p. 195-196). From this distinct trend in Irish Protestant magic, we get Sheridan Le Fanu's (1814-1873) Gothic tales and Bram Stoker's (1847-1912) incredible Dracula, brought to life by the sadly departed Christopher Lee (1922-2015). Yeats was part of this trend. With his interest in magic, he immersed himself in a hybrid of eastern and western traditions which enabled mental resilience and transformation.

An apocalypse is a narrative about extreme difference and war which ironically reaffirms a common psychology across cultural rifts and conflicts. For those who fear change, the myth of final spiritual war perhaps allows the ability to reconcile the irreconcilable. By subscribing to the same core end-of-the-world myth as their greatest enemies (although they disagree on details, especially who will emerge triumphant), eschatologists unconsciously acknowledge their common humanity with the people from whom they are most alienated. Armageddon plants the seeds of future peace and prosperity.

Yeats was interested in establishing that the psychological turn could be regarded in universal terms. He joined the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in March 1890. In 1899, he published The Wind among the Reeds, which you can hear as an audiobook here, and read for free online here or here. A typical passage from The Wind among the Reeds shows how Yeats connected local folklore to a much larger arcane body of knowledge, even at this early stage:

November, the old beginning of winter, or of the victory of the Fomor, or powers of death, and dismay, and cold, and darkness, is associated by the Irish people with the horse-shaped Púcas, who are now mischievous spirits, but were once Fomorian divinities. I think that they may have some connection with the horses of Mannannan, who reigned over the country of the dead, where the Fomorian Tethra reigned also; and the horses of Mannannan, though they could cross the land as easily as the sea, are constantly associated with the waves. Some neo-platonist, I forget who, describes the sea as a symbol of the drifting indefinite bitterness of life, and I believe there is like symbolism intended in the many Irish voyages to the islands of enchantment, or that there was, at any rate, in the mythology out of which these stories have been shaped. I follow much Irish and other mythology, and the magical tradition, in associating the North with night and sleep, and the East, the place of sunrise, with hope, and the South, the place of the sun when at its height, with passion and desire, and the West, the place of sunset, with fading and dreaming things.

Image Source: Irish Central.

The Wind among the Reeds abounds with stories which ask the reader to doubt the superficial: demon-people could deceive the eyes, even residing in villages as false normal folk, until one day they inexplicably disappeared, or demon-animals took the guise of frightening pigs, or mer-people were spied by sailors as storms blew in:

The poet loved the environment - twilight, moonlight, hills, moors, swamps, wind, sea - and he studied local beliefs in nature spirits. But Yeats constantly transported these elements to the universal level, via the legends of the ancient Greeks, or through the rites of a 'mystical brotherhood.' He sought eternal stories, the final psychic archetypes behind the myriad manifestations of divinity, rituals and superstitions. For example, a seaside town will always have a love-hate relationship with the water and monsters to match, whether in Beowulf or John Carpenter's The Fog (1980).The Tribes of the goddess Danu can take all shapes, and those that are in the waters take often the shape of fish. A woman of Burren, in Galway, says, 'There are more of them in the sea than on the land, and they sometimes try to come over the side of the boat in the form of fishes, for they can take their choice shape.' At other times they are beautiful women; and another Galway woman says, 'Surely those things are in the sea as well as on land. My father was out fishing one night off Tyrone. And something came beside the boat that had eyes shining like candles. And then a wave came in, and a storm rose all in a minute, and whatever was in the wave, the weight of it had like to sink the boat. And then they saw that it was a woman in the sea that had the shining eyes. So my father went to the priest, and he bid him always to take a drop of holy water and a pinch of salt out in the boat with him, and nothing could harm him.' The poem was suggested to me by a Greek folk song; but the folk belief of Greece is very like that of Ireland, and I certainly thought, when I wrote it, of Ireland, and of the spirits that are in Ireland.

Yeats and Mysticism. Video Source: Youtube.

How did that continuity of psychological archetypes relate to the movement of time? In 1925, Yeats privately published A Vision: An Explanation of Life Founded upon the Writings of Giraldus and upon Certain Doctrines Attributed to Kusta Ben Luka, which was a major exposition of his search for the interaction between archetypal symbols and the human consciousness of reality. Relying on an occult order, A Vision depended on the psychic reports of Yeats's much younger new wife, Georgie, as she experimented with automated writing.

Yeats with his wife, Georgie Hyde Lees (1892-1968), in 1923. Image Source: The Archivist's Corner.

Over a period of five years at the start of their marriage, George channeled messages to Yeats from the spirit world. She also channeled her own concerns to him. Her episodes of spirit writing - which at their height reached two sessions per day - stopped after she gave birth to their second child, a much-hoped-for son (Maddox, George's Ghosts, p. xviii). Biographer Brenda Maddox believes that there were never more than two people in the room in these sessions, which were simply a cryptic way for the two to communicate (Maddox, George's Ghosts, p. xix). Nevertheless, the mystical ritual, in which George produced thousands of pages of raw symbolic notes, was the basis for some of Yeats's greatest work. This Public Address explains:

There were plenty of idiosyncrasies around the poet besides Georgie's automatic writing, including Yeats's acquaintance with Madame Blavatsky in the 1890s. There was his 1934 Steinach operation - in the days before viagra, which was notoriously rumoured to be a monkey testicle transplantation. It was actually a vasectomy; you can read more about Yeats's sexual rejuvenation procedure here. He also had some weird extra-marital adventures. Through it all, psychic and physical experiments offered Yeats ways to understand how human psychology tapped the order of the universe.The book was first printed with an introduction that was an elaborate subterfuge. Yeats describes how a book of metaphysical lore was passed on to him by a mysterious traveler from the east. It was written by Giraldus in Cracow in 1594, and it contained the system which Yeats had transcribed as A Vision. This was Yeats’s story in 1925.In 1938, Yeats recanted through an epistolary preface entitled “A Packet for Ezra Pound,” telling the “true” source of the information in the book. He transcribed it from “spirit communications” which his wife produced through automatic writing while in a trance. The 3,000 pages of transcription of this "miracle" were eventually published separately as well, to try to lend credibility to Yeats's story. This book supposedly has its origin in “the other side.”

For Yeats, that relationship between psychology, consciousness and the nature of the universe followed gyres of history. Each gyre, which ran its course over a period of 2,000 years, had a contrasting spiritual 'flavour' to its predecessor. These two-millennia cycles would continue until their combined time reached one Great Year of 26,000 years, whereupon the overall cycle would break into a new stage in human evolution. You can read further on Yeats's understanding of time here, here and here. Below, you can trace the conceptual evolution of a series of alchemical, religious and magical images leading up to Yeats's invention of gyres of time.

"The Joust of Sol and Luna from Aurora consurgens (15th/early 16th century); note that Sol’s shield has a lunar emblem, while Luna’s shield carries a solar one."

Image from: Rosarium Philosophorum (1550). "The most basic tenet of alchemy is that there are two primary ways of knowing reality. ... The first way of knowing is rational deductive, argumentative, intellectual thinking that is the hallmark of science. ... The alchemists called this solar consciousness, and assigned it many code words, such as the King, the Sun, Sulphur, Spirit, the Father, and ultimately the One Mind of the universe. ... The alchemists called the other way of knowing lunar consciousness. This intelligence of the heart is a non-linear, image-driven intuitive way of thinking that is an accepted tool of the arts and religion. Among its many symbols are the Queen, the Moon, the metal Mercury, the Soul, the Holy Ghost, and ultimately the One Thing of the universe." (Yeats Vision citation of Andrea Aromatico, Alchemy: The Great Secret, translated by J. Hawkes (New York: Harry N. Abrams Inc., 2000), 45).

"Detail (lower portion) of Mathieu Merian’s engraving prefacing ‘The Philosophical Basilica’ of Daniel Mylius’ Opus medico-chymicum (1618)."

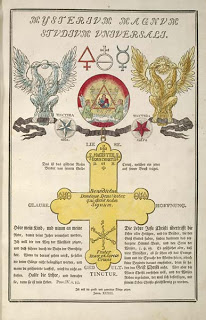

Geheime Figuren der Rosenkreuzer, aus dem 16ten und 17ten Jahrhundert (Hamburg: J. D. A. Eckhardt, 1785).

Above, earlier sources that inform Yeats's understanding of gyres of time. See Rosicrucian sources here and here. Images sourced from: Yeats Vision, Ignis et Azoth, University of Wisconsin Digital Collections and tumblr.

Graphic and symbolic interpretations of Yeats's gyres of time and experience, explained in A Vision (1925), often mapped onto earlier diagrams, expressing a continuity of thought on the subject. Images Sources: Ali Scot, This Public Address, Times Literary Supplement, Sebastian and Stephanie Mahfood, and Yeats Vision.

Yeats's understanding of the gyre of time always mirrored spiritual challenges at the level of the individual mind, where every single person on earth faced echoes of the universal spiritual shift. This was why he followed an occult hierarchical path of what we would call personal development, its stations marked by the tree of life. Yeats's A Vision, based on his wife's mystic communications, tied his cyclical view of history to psychological and spiritual changes. In this manner, he attempted to explain contemporary conflicts, as well as the huge impacts violence and unrest had on his immediate friends and acquaintances. BBC:

"The gyre ... along with the cyclical view of history it embodies, belongs to the complex system outlined by Yeats in A Vision. This figure is true also of history, for the end of an age, which always receives the Revelation of the character of the next age, is represented by the coming of one gyre to its place of greatest expansion and off the other to that of its greatest contraction. At the present moment, the Life Gyre is sweeping outward, unlike that before the birth of Christ, which was narrowing, and has almost reached its greatest expansion."

Cover illustration of Thoor Ballylee by Thomas Sturge Moore of the first edition to Yeats's The Tower. "The tower mirrored in the stream illustrates the neo-platonist concept of a mirrored universe: 'As above, so below.'" (Maddox, George's Ghosts, plate 33). Image Source.

In 1928, Yeats published a poetry collection entitled, The Tower. In older Tarot decks, the trump, 'The Tower' is also called 'The House of God.' Image Source: Yeats Vision.

Puxley Mansion, one of hundreds of Anglo-Irish estate houses burned out by the IRA in the early 1920s. Image Source: Spicy Noodles.

In The Tower, Yeats, who felt he was getting on a bit, wondered about old age. He attacked inflexible dichotomies between mind and body, thought and action, and sought some greater consciousness through poetry. The Tower is a Tarot trump card which is a station in the individual development of a ritual initiate who is following the aforementioned path of the tree of life: "The Tower ... represents the fall of earthly attachments and false structures of the egotistical mind. The lightning bolt is wisdom from the Higher Self, displacing the crown." And the image of the Tower gained weight in Yeats's real world as the Irish Republican Army burned of over 270 Ascendancy manor houses from 1919 to 1923.

An orientalist theme also appeared in this collection, in the poem Sailing to Byzantium (1928) and its reworked version, Byzantium (1931). These poems projected psychological, real and symbolic cultural conflict that onto a spiritual struggle and resolution. Incidentally, the phrase 'no country for old men,' which was used as the title of the Cormac McCarthy novel of 2005 and the adapted American Coen brothers' movie of 2007, is from the opening line of Sailing to Byzantium.

Brian Bauld explains that magic effects a miraculous transition between tool or artifact and the imagined-made-real. The difference was that Yeats did not want to make myths reality (as one might argue ISIS is today). In other words, Yeats was not trying to raise some Antichrist or anti-Antichrist with his poetry. The symbols of spiritual language were not meant to be read literally. They were part of a creative process. Yeats wanted to deepen a countervailing consciousness against violence and hatred. He wanted to make awareness real. The temporal counterpart to that transition runs from mortality to eternity: layers of telescoping awareness resemble Yeats's gyres of time. In parallel, the poet's artistic works transcend the limited existence of the poet. The late Yeatsian vision is of a cosmic foundry, where immortal consciousness is being moulded into actuality:

Yeats envisioned these alternate indelible realities just as his own world was smashed apart. It is hard to underestimate the impact of the Irish conflict on him. The whole establishment to which Yeats belonged was destroyed or absorbed into an emerging, modern, and fatally divided Ireland. Yeats kept searching for a third way, which depended on mystical spirituality, awakened and preserved over vast stretches of time. Through the Easter 1916 uprising, Yeats supported Irish nationalism, but he was increasingly disturbed by the spread of terror and brutality, the aesthetic violence of modern Irish conflict. His concerns rose as he saw the impact on his friends and family (many of whom emigrated).A most central fact appears when, for the first time, the poet actually experiences or is confronted by the eternal city's reality. The old man of Sailing to Byzantium imagined the city's power as being able to "gather" him into "the artifice of eternity" -- presumably into "monuments of unageing intellect," immortal and changeless structures representative of or embodying all knowledge, linked like a perfect machine at the center of time. Yeats perfects and makes startlingly real what was previously only imagined as perfect when, in Byzantium, he seems to envision an actual artifice of eternity and not eternal artifice. The city, as we shall see, generates -- or actually smelts -- eternal images: lifeless and deathless realities which finally supersede or consume all "complexities," all individual souls, all art, all the forms of temporal life. This contrast between the two poems is central to Yeats's re-imagining of his former theme. ...Of the two cities [of Byzantium] envisioned in the poems, Harold Bloom writes in his book Yeats that "The cities are both of the mind, but they are not quite the same city, the second being at a still further remove from nature than the first." This is clear, and it is relevant to the status of each vision. After reading both poems it is possible to conclude that, were the speaker of the Þrst poem to die, both his soul and the raw matter of that poem's entire vision of Byzantium would be consumed within the eternal fires of the second poem, inside the reality of the city. This city is "at a further remove from nature" because it is about as inhuman and unnatural a state as it is possible to conceive of -- as eternity actually would be, even fully so, if we could conceive it fully. Again it is important to note that the later poem does not present the city as it is imagined to be, but as it really is, at least in the context of the two poems; there is no mediating or poeticized character to limit the voice or devalue the status of the vision as simply and consciously imagined within the poem's reality. Nor does the reader feel in the second poem any of the pathos or irony of what was (because imagined and sought by a living human being and not a soul) a deeply suicidal, yet artistically driving, vision. ...Byzantium is a less human vision than all this; finally, for the soul, there is nothing whatsoever of this kind of remorseless triumph, absolute knowledge, or personal perfection in the machinations of that which is eternal in art. The city is more like a physical process than a state of knowledge, and yet the reader must try to imagine it as a process so basic that it makes void all "complexities," those qualities of nature and reality which we cannot even conceive as being absent, and indeed, without which we cannot conceive at all. As in a perpetual furnace or process beyond all time, matter, and human conception, in "Byzantium" we behold not fixed form and matter which can perfect and eternalize the temporal, but eternally unliving undying images, the action or nature of which consumes and nullifies all artifice, all things real or imagined.

With all his dabbling in the occult, it would be ridiculously easy (and wrong) to dismiss Yeats's arcane system as hocus pocus and anti-Christian. It was more that Yeats had extended his temporal horizons, and attempted to reconcile the fading Christian gyre with the coming anti-Christian gyre. He was Protestant, but Irish, delighting in the pre-Catholic traditions of the Catholic peasantry. He kept searching, using his magic tools and his wife's mystical help, for some point of Irish unity that reached back on a long enough timeline, beyond memory and history. He dreaded a violation of the Irish spirit, something pure, organic and sacrosanct. His poems were magical spells crafted to invoke this great spirit of Ireland, the heart of a beautiful, wild land surrounded by the sea. Yeats had won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1923 after the War of Independence, and the message of the committee was clear. The award went to him: "for his always inspired poetry, which in a highly artistic form gives expression to the spirit of a whole nation." Yeats's worldly attitudes as an individual and politician were far (far!) from perfect. But they were broken pieces of a much larger project. That project involved an artist, fighting with all his power to protect Ireland's soul, and using the forces of creation to prevent its destruction.

In that sense, Yeats continued the message implicitly conveyed by Shelley in Ozymandias, where the artistic creation transcended its subject, and brought its subject back to life, but only on the condition that the artistic vehicle in which the thing was presented would always be freer, more eternal, eluding petty categorization, and remain infinitely more powerful than any pathetic, limited stone-throwing political discourse. On the latter level, Yeats's personal attitudes were classist and patriarchal. To conjure up Shelley's higher levels of art and creation, Yeats indulged the ugly. His poems are beautiful, but they weren't devoted to the ethos of 'beautiful art.' Art could be hair-raising, frightening and harsh. Even Yeats's earliest works saw him accept unlikely, weird, hostile symbols. These symbols would arise (as if by magic) in times of fear and trouble, to aid in the creation of a bigger picture, which always had a redemptive kernel of truth. The Celtic Twilight piece, Belief and Unbelief, concluded:

Prior to the revolutionary guerilla war against British rule, in 1919, one could dismiss Yeats's personal focus as petty, unrealistic and bizarre. He was preoccupied with his ranking in the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn; he wanted just the right robes designed for his promotion as 'Chief Wizard.' There were laughable incidents, such as Yeats's 1917 trip to the Sussex coast with the director of London's School of Oriental Studies, Edward Denison Ross, to investigate a talking Turkish copper box that was supposed to predict the future (Maddox, George's Ghosts, p. 3-4). Yeats later defended his interest in shamanic, sacred magic over and above simple political ideas:It is better doubtless to believe much unreason and a little truth than to deny for denial's sake truth and unreason alike, for when we do this we have not even a rush candle to guide our steps, not even a poor sowlth to dance before us on the marsh, and must needs fumble our way into the great emptiness where dwell the mis-shapen dhouls. And after all, can we come to so great evil if we keep a little fire on our hearths and in our souls, and welcome with open hand whatever of excellent come to warm itself, whether it be man or phantom, and do not say too fiercely, even to the dhouls themselves, 'Be ye gone'? When all is said and done, how do we not know but that our own unreason may be better than another's truth? for it has been warmed on our hearths and in our souls, and is ready for the wild bees of truth to hive in it, and make their sweet honey. Come into the world again, wild bees, wild bees!

If the poet really could have seen the future, the Troubles in Northern Ireland in the decades after his death, it would have made his sense of purpose even more desperate. Today (13 June 2015), the BBC broadcast a piece criticizing Gerry Adams on its show, Storyville Global, entitled Disappeared by the IRA. The show suggested that Adams, now a groomed, respectable statesman, allegedly once a member of the IRA, personally ordered the murders and disappearances of informant Catholic and British Army targets during the Troubles in the 1970s and 1980s. In a BBC interview, Adams denied all allegations made by supposed former IRA associates. Whatever the truth may be, he made a telling remark, suggesting that political realities are never built on the moral values they claim to uphold. He stopped the interviewer and said: "Do you not live in the real world?" That is the real world, where the British government after centuries of suppressing the Catholic peasantry, was mostly driven out of Ireland; and in its northern rump state (torturously run by radical Protestants), it had to make deals with murderers to make peace in the 1990s.Yeats made it clear how he considered his study of the magical: "Now, as to magic, it is surely absurd to hold me weak or otherwise because I choose to persist in a study which I decided deliberately ... to make, next to my poetry, the most important pursuit of my life. The mystical life is the centre of all that I do, and all that I think, and all that I write.

It is ironic that Yeats might be dismissed for his mystical interests, when real world politicking conjures up illusions of order by making deals with devils. Decades before, Yeats had witnessed the birth of the IRA; some of his Protestant Anglo-Irish friends took part in its formation. The BBC show confirmed that some of the IRA's most fearsome tactics had already appeared in the 1920s. Is it any wonder Yeats retreated into the fantasy of an over-idealized past, into a hope where the dreams of Irish people would not be hammered by 'ends-justify-the-means' politics into something profane, so that the country in the end would be built neither by British soldiers presiding over torture chambers, nor by IRA liars, over fields filled with disappeared bodies?

Family, Folklore and Irish Nationalism

Merville (now Nazareth) House, which belonged to Yeats's maternal grandfather, where the poet spent parts of his childhood.

Merville House in the 1870s, as it was when Yeats visited it.

Since Yeats defined time in terms of psychology, we need to ask what shaped his psychology. The above accounts of Yeats's late works show that a journey through time is a journey into the soul, which begins with family. And to understand a family, you need to step back into the interiors of a house. Above is a photo of Merville House, owned by Yeats's no-nonsense maternal grandfather in County Sligo, in the town of the same name on the western coast of Ireland. This was where his mother's family had a profitable shipping business.

Yeats's odd combination of social snobbery, idealized aristocrats and artistic transcendence grew out of his parents' marriage. His mother, Susan Pollexfen, considered in her youth to be "the most beautiful woman in Sligo," married his father, John Butler Yeats, after a short courtship and an 1863 marriage which both later regretted. The poet's father, an Anglo-Irishman from a socially respected and genial family with a landed estate, initially won approval from his commercially-minded in-laws, until he suddenly abandoned a promising legal career in 1867 for an artistic one. In so doing, he bitterly disappointed his wife, who was used to a comfortable, stable life, rather than the impoverished precarious one he ended up providing for her. Of his wife, John said: "I always hoped she was not as unhappy as she seemed."

Conventional success meant nothing to J. B. and everything to his wife. He lived on hope, philosophy and wild ideals and held forth at the supper table "like the Ancient Mariner ... [while] Mama dined alone upstairs." William Butler Yeats told a friend that his father disliked conventional work:

"Papa looked upon ordinary work - the nine-to-five job - as 'evil' and hoped something would come along to make it 'unnecessary.' ... When ... [William] rejected an offer to write for the Manchester Guardian his father was relieved, saying, 'You have taken a great weight off my mind.'"William was his mother's least favourite child because he inherited so many of his father's artistic tendencies. J. B. was proud of all of his four surviving children. He drew many portraits of them and of his glacial wife, and his depictions show care and sensitivity. The NYT quotes J. B.'s observation that his silent wife had a deeply emotional soul:

The family stayed together, in spite of financial stress and emotional strife, and William lived with them until he was thirty years old. All the children pursued the arts. William co-founded the Irish National Theatre in 1904 and won the Nobel Prize in Literature. The sisters, Lily (1866-1949) and Lolly (1868-1940), significantly contributed to the Celtic Revival of art and traditional Irish crafts; in London, they were members of the Arts and Crafts Movement led by William Morris. The youngest, Jack (1871-1957), was an artist, illustrator and 1924 Olympic medalist for his artwork (at that time, art was part of the Olympic competitions).[S]he hated what she construed as the pretensions and social frivolity of 'artistic' life. Nor did she share the Yeats fascination with how people behaved: like her brother George, she put up barriers. "All the time the [Pollexfens] were longing for affection," JBY thought, "and their longing was like a deep unsunned well. And never having learned the language of affection they did not know how to win it. It is a language which, like good manners, must be learned in childhood. I more than once said to my wife that I never saw her show affection to me or to anyone, and yet it was there all the time."

Crushed by the lack of money and respectability, Susan faded into the background, inert, bitter and lost in depression which eventually consumed her, while her husband struggled to build an artistic practice in London. The children hated London. Yeats stated:

"What a horrid place this London is!" "I sometimes imagine that the souls of the lost are compelled to walk through its streets perpetually. One feels them passing like a whiff of air."It was by virtue of J. B.'s financial problems that the family periodically left London and spent time living at the mother's family home, Merville House. There, they were drawn into the world of the Pollexfen family. J. B. pegged his wife and in-laws with far more sympathy than he received from them. He found the Pollexfens to be endlessly interesting, even when they chose not to be interesting. J. B.'s comments show a bright, resilient and sentient wit, which makes us more inclined to believe his opinions.

J. B. saw the Pollexfens as internally inconsistent, overtly fixated on property, money, class and business, they nonetheless had huge artistic impulses which they could not find a way to express. Reserved, moralistic and respectable, their knack for business overshadowed innate talents for art, music and rhyme, along with repressed feelings which dragged some of them into madness. J. B. saw in all of them, even the most ruthlessly practical ones, a hugely compelling charismatic magnetism and enormous "primitive" artistic potentials. They dreamed of white seabirds when another member of the family died. They somehow embodied a "mysterious energy," a "pulse of universal life." But they were voiceless and repressed about it. J. B. was proud that his free spirit qualities had somehow provided the essential ingredient to ignite their mother's vast potential in his children:

"The Pollexfens are as solid and powerful as the sea-cliffs, but hitherto they are altogether dumb. To give them a voice is like giving a voice to the sea-cliffs. By marriage to a Pollexfen I have given tongue to the sea-cliffs."Susan Pollexfen's mood only recovered when the family returned to Merville House. At these times when her spirits improved, she told Irish fairy tales to Yeats and his siblings, and her rare animation left a deep impression on them (Murphy, Family Secrets, p. 1, 15, 19-22, 37, 46, 57, 59-61).

Thus, although Yeats's mother was a distant figure compared to the later women who figured in his life, it was she who taught him to bear witness to, and love, the elemental Irish spirit. It is a curious circumstance, given that his father was the 'artistic one.' For W. B. Yeats, the Pollexfens' excursions into the arts were as rare as they were electrifying. His Pollexfen aunt, Isabella, was the first person to introduce W. B. to the occult, and gave him a copy of A. P. Sinnett's Esoteric Buddhism (1883).

Interior hallways of Nazareth (Merville) House today.

Yeats's early poems mined Irish fairy tales and folkore, He paid homage to the servants' chatter in the back kitchens at Merville House. All four Yeats children remembered:

[T]hose of the lovely town [of Sligo] and the surrounding countryside, of the Irish servants and their charming superstitions, their belief in fairies and fairy raths, in a world that held mystery and meaning for its inhabitants. At Merville, [Yeats's sister] Lily wrote, "The servants played a big part in our lives. They were so friendly and wise and knew so intimately angels, saints, banshees, and fairies." ... Even in their old age the memory was still strong. "I get a longing often to see the waves roll in at Rosses Point," Lily wrote to her cousin Ruth in 1926, "to walk there on the Greenlands with the carpet of tiny flowers, wild thyme, lucky Larry, pansies, white clover ... like jewels. To see Ben Bulben so majestic." ... The Sligo of their childhood became to William Butler Yeats an ideal land, a dream world to which, though once an inhabitant, he could never return, a Paradise not to be regained. (Murphy, Family Secrets, p. 32-34)Yeats edited a book of Fairy and Folktales of the Irish Peasantry. It recounts his interviews with local folk, for whom superstitions and natural gods were alive. In the preface of this work, Yeats reported that he had interviewed a girl in Country Dublin: Did the men from County Dublin ever see mermaids? The answer came: "Indeed, they don't like to see them at all, for they always bring bad weather." This early period of Yeats's work is elegant and elemental, inquiring, gentle and reserved as he touched on Irish home, hearth and tradition. The environment is closed, intimate, its magic conveyed through an abundance of natural details and the faith those details inspired in the common people.

County Sligo landscape: view from the back of Temple House of the ruins of the castle built by the Knights Templar. Image Source: Home Thoughts from Abroad.

R. F. Foster explains Yeats's depiction of faerie lore, a symbolic code for the hidden taboos and violence of impoverished country life (incest, anorexia, child molestation, disappearances and mysterious deaths, violence, crime, politics), where lives are lived "in parallel" with an occult or supernatural dimension such as doublings and hauntings (2011). Video Source: Youtube.

The Devil, excerpt from The Celtic Twilight (1902) by W. B. Yeats (read it online for free here, you can listen to the free audiobook here), in which Yeats anecdotally described the superstitions which dominated rural Ireland in his youth. Video Source: Youtube.

The wilderness stands in contrast to the mechanistic encroachments of the modern world. Here the Romanticism of the early 19th century survives, still rejecting the Enlightenment, and hails a natural world that is still king, where old gods rule. The moonlight, stars, water and trees are all animated entities, possessed by spirits with unnameable desires. Superstitions survived in peasant culture into the poet's present. You would only need to walk down a lonely county road, or wooded path, and the innumerable defenses and conveniences which people construct against the wilds no longer provide any protection.

In the early Yeats, a lyric poem such as The Song of Wandering Aengus (1899) depicts the Irish god of love, Aengus, searching for his love while the natural world predominates. Even at this point in Yeats's writing, everything hinges on the natural-turned-magical: "The silver apples of the moon, The golden apples of the sun." Only later did Yeats expand the mythos from Ireland to the globe.

Today's New Age advocate regards the natural world with unquestioning reverence. In countless political narratives, the environment plays the universal victim; she is a violated, raped and silenced presence, symbolized above all by the permeated astmospheric ozone layer. In Yeats's earlier period, the natural world retained its threatening power and mystery, as in The Stolen Child (1886-1889). It could also be a source of vitality and peace, as depicted in The Lake Isle of Innisfree (1888-1890).

The Stolen Child (1886-1889), this video, read by Anya Yalin, was made in 2009 in the virtual reality environment, Second Life. Loreena McKinnitt put the poem to music (here) in 1985. Video Source: Youtube.

Analysis of The Stolen Child (1886-1889) by Hazel Dempster (2013). Video Source: Youtube.

Yeats indulged in the occult and fairy tales, but he walked a fine line between being seduced by these superstitions and quasi-religious alternatives, and using them as a poetic explanations of psychology. The seductive draw of these stories was as important as the superstitious body of belief. With fairies and occult symbols in fact portraying real psychological damage, yearning and obsession, Yeats turned toward the modern. A Youtuber argues that The Stolen Child is not really about fairies luring away a child; nor is it even a cryptic representation of a village scandal, wherein a child has disappeared or been kidnapped. The Stolen Child is about the psychological shock a child faces when confronted with the spectre of adulthood. At this liminal moment, the child's natural response is escapism and arrested development:

He's talking about the inevitable heartbreaking loss that all children experience within themselves when they move into adulthood. He's talking about how they want to remain children, how they're not ready, and how the perceived violence of the adult world makes them want to walk away into the water and the wild, and, actually, its safety.The portrayal of the child being lured away from average, everyday life and its sensible monotony resonates today. The seduction of the innocent using "stolen cherries," almost echoes today's beckoning fame and fortune, especially in the entertainment industry. But it could also mirror today's financial troubles, caused when people are asked to borrow against the future to conjure up a materialist fantasy life they can never afford. Do you fall for the fantasy? The Stolen Child warns: fantasy worlds promise a lot but are actually exploitative and sinister, and human life is cheap there.

Yeats's The Lake Isle of Innisfree (1888-1890), read by Tony Britton (2011). Video Source: Youtube.

The Guardian on The Sorrow of Love: "This early masterpiece combines great symbolic resonance with pin-sharp observation of the natural world." Yeats's poem, The Sorrow of Love (1893), set to music. Video Source: Youtube.

Love was part of Yeats's fascination with the natural world. It was also a source of enormous personal frustration and tension for him. He was famously rejected by the woman whom he felt was his soulmate, the Irish nationalist revolutionary, Maud Gonne (1866-1953); after she turned him down, he creepily proposed to her beautiful daughter, who also rejected him.

Yeats was captivated by Gonne's critical friendship and romantic rejection, perhaps because it was reminiscent of his mother's distance from him. Gonne's strong Edwardian, handsome beauty fascinated him because of its bow-tight tension, full of stubborn potential for happiness, perhaps, or more likely strength and sorrow. In Yeats's frustration and friendship with Gonne, the latter put up a wall of resistance that the poet found mesmerizing. Although he was jealous of her husband, he included him among those honoured in his poem, Easter, 1916 about the nationalist uprising against the British.

THE SORROW OF LOVE (1893)

The brawling of a sparrow in the eaves,

The brilliant moon and all the milky sky,

And all that famous harmony of leaves,

Had blotted out man's image and his cry.

A girl arose that had red mournful lips

And seemed the greatness of the world in tears,

Doomed like Odysseus and the labouring ships

And proud as Priam murdered with his peers;

Arose, and on the instant clamorous eaves,

A climbing moon upon an empty sky,

And all that lamentation of the leaves,

Could but compose man's image and his cry.

In The Celtic Twilight (1902), The Untiring Ones, Yeats states that fairies are able to accept totalities, whereas human reality is always mixed, mitigated, full of mess and conflict. Fairy emotions are uncomplicated, absolute, eternal. This suggests that the poet, in writing poetry is seeking to find that mystical realm of complete perfection or unmediated emotion in his art, unlike everyday life, where one has to compromise, or grow old, or forget, or become wretched:

With this passage, Yeats again revealed why the world of folklore, fairies, and by extension occult mysteries were so attractive to him.It is one of the great troubles of life that we cannot have any unmixed emotions. There is always something in our enemy that we like, and something in our sweetheart that we dislike. It is this entanglement of moods which makes us old, and puckers our brows and deepens the furrows about our eyes. If we could love and hate with as good heart as the faeries do, we might grow to be long-lived like them. But until that day their untiring joys and sorrows must ever be one-half of their fascination. Love with them never grows weary, nor can the circles of the stars tire out their dancing feet.

Maud Gonne. Image Source: pinterest.

Yeats on Maud Gonne: "I had never thought to see in a living woman such great beauty." Image Source: Orna Ross.

For decades, Yeats had built his pro-Irish nationalism out of a love of Celtic folklore and the landscape and peasants' traditions of County Sligo; but at the end of his days, he emerged as a Protestant liberal with aristocratic fascist leanings. He and his contemporaries came through a period of immense Irish turbulence. After an Irish Republic was declared in 1919, two years of guerrilla war saw Home Rule fail in Southern Ireland. British plans in 1920 to keep Southern Ireland part of the UK collapsed, and Northern Ireland became a centre of UK loyalty and conflict - shaped by an Orange Protestant furor and a Republican ruthlessness. Yeats identified with none of it. The Irish Free State was established by 1922. Yeats was a member of first Irish Senate from 1922 to 1928, but the new order intensified his old, defensive class snobbery. R. F. Foster explains how the Catholics watched the Protestants of this stripe, from different classes and backgrounds, merge into one forsaken elite, still laying claim to a certain elemental thread of Irish identity:

An Irish Protestant identity isn’t necessarily what you’d expect of a nation-building Irish nationalist. And traditionally, the self-consciously Protestant Yeats emerges only in the 1920s: when, sixty years old and after a lifetime of ostentatious Celticist and nationalist sympathy, he turned on the Catholic guardians of morality in the new Irish Free State and assailed their outlawing of divorce. Suddenly Yeats invoked the tradition which bore him: Protestant liberalism. ... Irish Protestantism, even in its non-Ulster, non-demotic mode, is as much a social and cultural identity as a religious one, and ... [is] a more complex formation than often realised. In his triumphalist and stately post-1920s Ascendancy style, Yeats celebrated his literary and theatrical partnership with Lady Gregory and John Millington Synge, where artistic commitment was shaped by the social identity of an élite."John Synge, I and Augusta Gregory, thought All that we did, all that we said or sang Must come from contact with the soil ... ."This picture disguises the variety of backgrounds, and the social fissures, represented by that formidable triumvirate of Abbey Theatre directors who formed the national theatre. Lady Gregory came from the world of country houses, vast Western estates, family retainers and imperial service. Synge was the descendant of Church of Ireland bishops and secure county gentry. Yeats’s forebears were merchants, rectors, professional men and lawyers. By the time of The Municipal Gallery Revisited (written in August 1937), social spaces between the various levels of Irish Ascendancy mattered less (there were so few of them left). And Yeats had elevated himself to their upper reaches by a sort of moral effort and historical sleight of hand. Much earlier in his career, however, he had been mercilessly mocked by the novelist George Moore (son of a Catholic Big House far grander than Lady Gregory’s). There is one famous account of Yeats crooning over the fire about his ducal Butler ancestors ... .

This assessment of Yeats's class pretensions is both accurate and unfair, since social meanings in that time and place had transformed beyond recognition, not just once, but many times across the decades as Ireland modernized into a separate state. Yeats may have had middle class roots, but he also had aristocratic ones, and he was anti-bourgeois (in a weirdly bourgeois sense), and inspired by Renaissance aristocracy. He projected this set of values onto his early life in the 1860s and 1870s. But there was a huge difference between actual life during those decades, and memories of life during those decades, when later remembered in the 1920s.Moore put it even more specifically and more offensively earlier in the same recollection, when he described Yeats at a public meeting to raise money for Hugh Lane’s collection of Impressionist paintings in 1904."[Yeats] began to thunder like Ben Tillett against the middle classes, stamping his feet, working himself into a great temper, and all because the middle classes did not dip their hands into their pockets and give Lane the money he wanted for his exhibition. When he spoke the words ‘the middle classes’, one would have thought that he was speaking against a personal foe, and we looked around asking each other with our eyes where on earth our Willie Yeats had picked up the strange idea that none but titled and carriage-folk can appreciate pictures. And we asked ourselves why Willie Yeats should feel himself called upon to denounce his own class, millers and shipowners on one side, and on the other a portrait-painter of distinction."As Moore pinpoints, the Yeats family, especially in the impoverishment spectacularly embraced by Yeats’s artistic father, existed historically at a different level from the Gregorys and even from the Synges - though by the twentieth century an overwhelming solidarity had had to assert itself, faced with the rise of Catholic democracy. This is one of the aspects not often remarked upon in analysis of the great correspondence between Gregory, Synge and Yeats. The shared dream of the noble and the beggarman also meant a shared exasperation with Catholic demos, and a refusal to allow that element the monopoly on being ‘Irish’. And this only clarified the lessons of Yeats’s childhood and background.

Michael Braziller and Eamon Grennan have summarized how Yeats yearned for an order crafted by idealized aristocrats, who could combine power and beauty with sprezzatura. Before the violence of the teens and twenties, this revolution was made by literary men and women. The revolutionaries created a revolution as a kind of cultural, symbolic and dramatic artifact, and the proper end of it was sacrifice. Yeats said Patrick Pearse, a leader of the Easter 1916 Rising, was half-whacked and wouldn't be happy until he was hanged.

Living history is quite different from thinking about it. The 1916 Rising brought Yeats back down to earth. Before the Easter Rising, revolution was an abstract, as were the world's unfolding conflicts. The poem, Easter, 1916, shows that for Yeats, history suddenly became personal. These were people he knew, some whom he admired, some he disliked. But they were real people, whom he had met in the streets of Dublin, with whom he had exchanged "polite meaningless words"; his daily reality was now in the history books.

The Anglo-Irish, radicalized and democratized: Constance Markievicz and her sister Eva Gore-Booth. Image Source: Sligo Heritage.

Constance Markievicz with her stepson Stanislaw and her daughter Maeve. Constance Markievicz (nee Gore-Booth) was a daughter of Henry Gore-Booth the Anglo-Irish landlord of Lissadell House. Image Source: Sligo Heritage.

Lissadel House today in County Sligo. Images Sources: Lissadel House and B and B Ireland.

In Memory of Eva Gore-Booth and Con Markiewicz (1927, published 1933), is a later poem by Yeats, in which the poet examines the aftermath of rebellion in Ireland, especially what happened to its Anglo-Irish participants and how much their world changed. Only some of these Protestants had supported the Catholic Irish nationalist cause. Essentially, this meant they threw their lot in with a movement that would finally destroy their society. They did so out of a sense of modern social justice and a commitment to the Catholic peasants. And they thought initially that Irish nationalism would result in a unified Ireland, still part of the UK, presided over by its own parliament via Home Rule. That did not materialize, and out of this first and most disastrous British experiment in imperial colonization came a republic. The early commitment of the Anglo-Irish nationalists was benevolently patriarchal. Sligo Heritage:

Contrasting the lifestyle of the privileged circles of the Ascendancy, in which her family moved, with those of their impoverished tenants Constance [Gore-Booth] wrote: ‘… Hidden away among rocks on the bleak mountain sides, or soaking in the slime and ooze of the boglands, or beside the Atlantic shore where the grass is blasted yellow by the salt west wind, you find the dispossessed people of the old Gaelic race in their miserable cabins.’

Constance Markievicz - Visit to a Dublin Family During the Tuberculosis Epidemic (1924) drawn by Constance Markievicz. Notes for the auction of this piece: "Tuberculosis, or TB, was a major cause of death among Dublin's poor during the early years of the last century. In 1912, it was reported that TB-related deaths in Ireland were fifty per cent higher than in England or Scotland. As a champion of the poor and disenfranchised, Constance Gore-Booth often visited families in the Dublin slums, bringing food and support. During the lock-out of 1913, she set up a kitchen in her basement to feed the unemployed, and later ... set up soup kitchens for poor schoolchildren in the city centre. Her death in 1927 was possibly the result of TB, contracted while visiting the families such as those depicted with such sympathy here." Image Source: Arcadja.

Later, these Protestant participants radicalized to prove their loyalty to aims removed from their original class and religious culture, but not alien to their Irish nationalist experience. To bridge religious divisions and a strict social hierarchy in a new order came at a cost. The 'before' photos above, and 'after' photos below, show something of the shock of modern and political transformation, which Yeats lamented. After his contemporaries, the sisters Eva Gore-Booth and Constance Markiewicz died, Yeats remembered them in a poem starting with an immortal image of them, sylph-like in youth, in their father's estate house of Lissadel. You can hear those idealized opening lines quoted by Canadian song-writer Leonard Cohen, here in a performance at the house in 2010. Wiki:

They are remembered in the poem as "Two girls in silk kimonos, both / beautiful, one a gazelle." Both later became involved in Irish nationalist politics, and Constance was sentenced to death for her part in the Easter Rising of 1916, though the sentence was subsequently commuted. Eva later became active in the Women's suffrage movement in Manchester, England.In the poem, Yeats laments the loss, not only of their physical beauty, but of their spiritual beauty – their later politics were far removed from the romantic ideal of Ireland that he had had in their youth. The second stanza speaks of the futility of their struggle, both his and the sisters', when the real enemy is time itself: "The innocent and the beautiful / have no enemy but time."

Constance Markiewicz's arrest mugshot after the Eastern 1916 Rising. She was in her late forties at this time. Even at this moment, Markiewicz dismissed her British captors with aristocratic haughtiness that lay beyond her conflicted social circumstances and sense of pure social justice. Image Source: Ireland Information.

Constance Georgina de Markievicz became the first woman ever elected to the British Parliament (1918-1922). For her participation in the Easter 1916 rebellion in Dublin, she was sentenced to death. She was also a socialist and campaigner for women's right to vote and was imprisoned in 1919, 1920 and 1923 for her fight toward these causes and Irish nationalism. A child of the aristocratic Protestant Anglo-Irish Ascendancy, she became known as the 'Rebel Countess,' and was further sentenced to hard labour for her support of Catholic Republicanism. She died at age 59, "penniless in an open ward in a public hospital on July 15th 1927." Image Source: Sligo Heritage.

Image of Constance Markievicz from The Tatler, 28 November 1917. Image Source: Kenneth Spencer Research Library.

Eva Gore-Booth (22 May 1870 – 30 June 1926), Irish poet (read some of her poems here), dramatist, suffragist, social worker and labour activist. She spent many years in Manchester working to alleviate the conditions of working women. Image Source: Lissadel House.

IN MEMORY OF EVA GORE-BOOTH AND CON MARKIEWICZ (1927)

The light of evening, Lissadell,

Great windows open to the south,

Two girls in silk kimonos, both

Beautiful, one a gazelle.

But a raving autumn shears

Blossom from the summer's wreath;

The older is condemned to death,

Pardoned, drags out lonely years

Conspiring among the ignorant.

I know not what the younger dreams –

Some vague Utopia – and she seems,

When withered old and skeleton-gaunt,

An image of such politics.

Many a time I think to seek

One or the other out and speak

Of that old Georgian mansion, mix

Pictures of the mind, recall

That table and the talk of youth,

Two girls in silk kimonos, both

Beautiful, one a gazelle.

Dear shadows, now you know it all,

All the folly of a fight

With a common wrong or right.

The innocent and the beautiful

Have no enemy but time;

Arise and bid me strike a match

And strike another till time catch;

Should the conflagration climb,

Run till all the sages know.

We the great gazebo built,

They convicted us of guilt;

Bid me strike a match and blow.

Great windows open to the south,

Two girls in silk kimonos, both

Beautiful, one a gazelle.

But a raving autumn shears

Blossom from the summer's wreath;

The older is condemned to death,

Pardoned, drags out lonely years

Conspiring among the ignorant.

I know not what the younger dreams –

Some vague Utopia – and she seems,

When withered old and skeleton-gaunt,

An image of such politics.

Many a time I think to seek

One or the other out and speak

Of that old Georgian mansion, mix

Pictures of the mind, recall

That table and the talk of youth,

Two girls in silk kimonos, both

Beautiful, one a gazelle.

Dear shadows, now you know it all,

All the folly of a fight

With a common wrong or right.

The innocent and the beautiful

Have no enemy but time;

Arise and bid me strike a match

And strike another till time catch;

Should the conflagration climb,

Run till all the sages know.

We the great gazebo built,

They convicted us of guilt;

Bid me strike a match and blow.

In 1925, Yeats argued in the Irish Senate against a ban on divorce. He protested against Catholic politics; he was not arguing exactly against Catholic values (although that was in there), but rather against Catholic authorities' use of religion as politics, in order to oppress the Protestant minority who disagreed with their values. These religious politics would lay the groundwork, Yeats argued, for visceral, innate, growing hatred and insoluble divisions between Catholics and Protestants. In a scandalously politically incorrect (but memorable) moment, he lauded the obliterated Anglo-Irish Protestant class:

It is perhaps the deepest political passion with this nation that North and South be united into one nation. If it ever comes that North and South unite the North will not give up any liberty which she already possesses under her constitution. You will then have to grant to another people what you refuse to grant to those within your borders. If you show that this country, Southern Ireland, is going to be governed by Catholic ideas and by Catholic ideas alone, you will never get the North. You will create an impassable barrier between South and North, and you will pass more and more Catholic laws, while the North will, gradually, assimilate its divorce and other laws to those of England. You will put a wedge into the midst of this nation. ...I think it is tragic that within three years of this country gaining its independence we should be discussing a measure which a minority of this nation considers to be grossly oppressive. I am proud to consider myself a typical man of that minority. We against whom you have done this thing, are no petty people. We are one of the great stocks of Europe. We are the people of Burke; we are the people of Grattan; we are the people of Swift, the people of Emmet, the people of Parnell. We have created the most of the modern literature of this country. We have created the best of its political intelligence. Yet I do not altogether regret what has happened. I shall be able to find out, if not I, my children will be able to find out whether we have lost our stamina or not. You have defined our position and have given us a popular following. If we have not lost our stamina then your victory will be brief, and your defeat final, and when it comes this nation may be transformed.

Ireland after the establishment of the new Irish Republic, shows the 1921 emergence of Northern Ireland, carved out of the old county of Ulster. Old County "Ulster (coloured), showing Northern Ireland in orange and the Republic of Ireland part in green." Image Source: Wiki.

Yeats was a clumsy and tone deaf political figure, possibly because language behaves differently in the political sphere than it does in the poetical one. He disliked raw democracy and saw socialism as "that mechanical eighteenth-century dream" from which would come the Antichrist of The Second Coming. In 1943, George Orwell counter-attacked and defended socialism by dismissing Yeats and the poet's magical thinking as follows:

Orwell was right about fascism! On the surface, his analysis of Yeats was also right. At the same time, he missed the fact that the poet's words and prejudices might have different meanings in a mystical context and in a different era. Yeats had once desired socialism, but it was of the artistic type conceived by William Morris. Morris was:As soon as we begin to read about the so-called system we are in the middle of a hocus-pocus of Great Wheels, gyres, cycles of the moon, reincarnation, disembodied spirits, astrology and what not. Yeats hedges as to the literalness with which he believed in all this, but he certainly dabbled in spiritualism and astrology, and in earlier life had made experiments in alchemy. Although almost buried under explanations, very difficult to understand, about the phases of the moon, the central idea of his philosophical system seems to be our old friend, the cyclical universe, in which everything happens over and over again. One has not, perhaps, the right to laugh at Yeats for his mystical beliefs — for I believe it could be shown that SOME degree of belief in magic is almost universal — but neither ought one to write such things off as mere unimportant eccentricities. ...Yeats’s philosophy has some very sinister implications ... Translated into political terms, Yeats’s tendency is Fascist. Throughout most of his life, and long before Fascism was ever heard of, he had had the outlook of those who reach Fascism by the aristocratic route. He is a great hater of democracy, of the modern world, science, machinery, the concept of progress — above all, of the idea of human equality. Much of the imagery of his work is feudal, and it is clear that he was not altogether free from ordinary snobbishness. Later these tendencies took clearer shape and led him to “the exultant acceptance of authoritarianism as the only solution. Even violence and tyranny are not necessarily evil because the people, knowing not evil and good, would become perfectly acquiescent to tyranny. ... Everything must come from the top. Nothing can come from the masses.” ...[A]s early as 1920 he foretells in a justly famous passage (“The Second Coming”) the kind of world that we have actually moved into. But he appears to welcome the coming age, which is to be “hierarchical, masculine, harsh, surgical”, and is influenced both by Ezra Pound and by various Italian Fascist writers. He describes the new civilisation which he hopes and believes will arrive: “an aristocratic civilisation in its most completed form, every detail of life hierarchical, every great man’s door crowded at dawn by petitioners, great wealth everywhere in a few men’s hands, all dependent upon a few, up to the Emperor himself, who is a God dependent on a greater God, and everywhere, in Court, in the family, an inequality made law.” The innocence of this statement is as interesting as its snobbishness. To begin with, in a single phrase, “great wealth in a few men’s hands”, Yeats lays bare the central reality of Fascism, which the whole of its propaganda is designed to cover up. The merely political Fascist claims always to be fighting for justice: Yeats, the poet, sees at a glance that Fascism means injustice, and acclaims it for that very reason. But at the same time he fails to see that the new authoritarian civilisation, if it arrives, will not be aristocratic, or what he means by aristocratic. It will not be ruled by noblemen with Van Dyck faces, but by anonymous millionaires, shiny-bottomed bureaucrats and murdering gangsters. ...How do Yeat[s]’s political ideas link up with his leaning towards occultism? It is not clear at first glance why hatred of democracy and a tendency to believe in crystal-gazing should go together. ... To begin with, the theory that civilisation moves in recurring cycles is one way out for people who hate the concept of human equality. ... Secondly, the very concept of occultism carries with it the idea that knowledge must be a secret thing, limited to a small circle of initiates. But the same idea is integral to Fascism. Those who dread the prospect of universal suffrage, popular education, freedom of thought, emancipation of women, will start off with a predilection towards secret cults. There is another link between Fascism and magic in the profound hostility of both to the Christian ethical code.

Perhaps the uniqueness of the poet's odd elitist idealism, misapplied to the political condition, is indicated by the fact that while Yeats leaned toward fascism in the 1930s, he was not an anti-Semite, unlike Ezra Pound, Maud Gonne and T. S. Eliot. Yeats was not talking about the violent politics of hatred and compromise in the material world. He sought to create a conscious state of being that might ease a darker psychological turn.a socialist of a theoretical sort, a dreamer of higher and better societies, and a practical handyman whose ideas of interior decoration ... were to influence taste permanently. ... [Yeats said:] "If some angel offered me a choice, I would choose to live his life, poetry and all, rather than my own or any other man's." (Murphy, Family Secrets, p. 63-64)