In pulp fiction, character-driven stories, so beloved from the 1970s to the mid-1980s, are now a thing of the past. For many years, but especially since about 2003, DC's comics universe has been awash in death, legacy characters doing the rounds in their fourth versions, dying, and coming back in fifth versions (see my blog entry on this here). DC’s two big events in 2009-2010, Blackest Night and Brightest Day, epitomize the morbid fascination with death and resurrection. Yet the leading lights of the company proclaim that these events in fact will halt the tide of death and reinvest it with meaning, a message that was carried out of Blackest Night. In BN issue #8, Green Lantern (Hal Jordan) announces that ‘dead is dead from here on out.’

While we wait for Brightest Day to deliver on writer Geoff Johns’s promise to give death meaning again, it’s obvious that DC and its competitor Marvel have a problem on their hands. During the Modern Age of Comics, which has run from the mid-1980s to the present, the mainstream comics companies painted themselves into a corner when they created the so-called ‘revolving door of death.’ Now, characters die so often in the name of ‘grim drama,’ that readers and critics cynically, or wearily, do body counts at the end of every crossover event. Why has DC killed off more than 650 (at latest fan count here at Legion World) of its characters since 2003? In all this overkill, the 2010 death of the young character Lian Harper aroused outrage at the company for gratuitously manipulating its readers, by taking excess to a new low. There is a deviantART site devoted to the topic here. Yet DC mistakenly took this emotional response to mean that its creative team had created a dramatic story that moved its readers, rather than comprehending that their audience was expressing annoyance and genuine death trope exhaustion. Why is DC so tone deaf when it comes to hearing what fans are saying? A flood of gore cannot be used to revive the seriousness of already-overused death memes that once were sacrosanct.

X-Men #136 (Aug. 1980)

There’s more to this than a vicious circle of commercialism. Let’s go back. The death of a hero in any medium, let alone in comics, was once the height of drama. It grew out of older roots in epics, fairy tales, literature and religious sources. It was a narrative line that was almost never crossed. It carried weight. And because it was a powerful dramatic tool, it was invariably a commercially successful plot device. Practically every comics fan recognizes the famous X-men cover of Cyclops holding a half-dead Jean Grey. The cover foreshadowed her death in the next issue, when she sacrificed herself to save the universe in the Dark Phoenix Saga. According to Marvel wikia, issue #137 from September 1980 was “the first time that a major Marvel Comics super-hero [wa]s killed off on-panel.” Jean Grey’s death might be considered a harbinger of the Modern Age.

Batman #156 (June 1963)

Aquaman #37 (Feb. 1968)

That image has its precedents and its successors:

Death of Supergirl, by Perez. COIE #7 (Oct. 1985)

There’s a good comment on the constant re-use of that image here. George Perez’s Webpage has a list of homage covers here. Even so, the image has changed over the years. At a glance, we can tell that in some of these pictures, the ‘dead’ character is ‘really dead’ and in others, although the image is identical, the character is ‘only unconscious’ or ‘not really dead.’

The Last Days of Animal Man #4 (Oct. 2009)

Homage to Perez, by Baltazar. Tiny Titans #29 (Aug. 2010)

Homage to Perez, by Groening, Delaney, Pepoy. Comic Book Guy #1 (Jul. 2010) © Twentieth Century Fox and Bongo Comics

Comic book death is so common that there is a lengthy Wiki entry on the subject here. Wiki notes that The Simpsons “parodied comic book deaths in the episode ‘Radioactive Man’ in which Milhouse mentions an issue of Radioactive Man in which the eponymous character and his sidekick Fallout Boy die on every page.” In 1991, Peter Chung did something similar with Aeon Flux, with Aeon dying repeatedly in a series of introductory shorts.

Death also dominates other branches of pop culture, whether it’s cinema, TV, video games and animation. The current vampire craze is one aspect of it. TV Tropes has a page devoted to the Death is Cheap trope and lists dozens of related memes: the Necromantic; Deader than Dead; Death is a Slap on the Wrist; Back from the Dead; the Sorting Algorithm of Deadness; the Sorting Algorithm of Mortality; Killed Off for Real; Red Shirt; Only Mostly Dead; Came Back Wrong; Tragic Dream; Things Man Was not Meant to Know; I Hate You Vampire Dad; Mummies at the Dinner Table; Resurrected Romance; No One Could Survive That; Left for Dead; Never Found the Body; Disney Death; Disney Villain Death; Our Hero is Dead; Tonight Someone Dies; Contractual Immortality; Opening a Can of Clones; My Death is Just the Beginning; Killed Mid-Sentence; Waking Up at the Morgue; Partly Cloudy With a Chance of Death; and You Shall Not Pass. The list goes on. And when it comes to fourth wall interference by writers in these matters, audiences and readers have to watch out for the Second Law of Metafictional Thermodynamics.

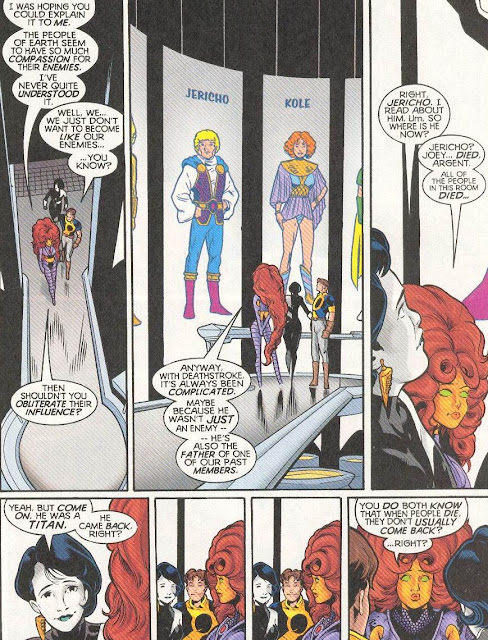

Why then, if everyone knows this, is death still considered a serious plotpoint inside superheroic stories? In the Teen Titans, the writer reached over the fourth wall recently when the character Starfire observes her younger heroic charges talking about dead characters (some of whom later came back). She says: “You do both know that when people die, they don’t usually come back, right?”

Titans vol. 1 #10 (Dec. 1999)

The more scepticism on the part of fans, creators, and even the characters themselves about the permanence of death, the more DC feels compelled to make death a momentous and serious matter for their characters. The characters have to be traumatized by death to the point where the readers actually feel something about it again (besides jaded annoyance). How to do that? Multiply death! Intensify it! That way we know it’s serious. It’s the Real Thing.

Girlfriend in a refrigerator. GL #54 (Aug. 1994)

One example of intensifying death is ‘fridging’ a character. In 1999, the comics writer Gail Simone coined the term ‘Women in Refrigerators’ to refer to Green Lantern #54 (August 1994), in which Green Lantern’s girlfriend is killed by the villain Major Force. Major Force then stuffs her body into Green Lantern’s refrigerator. This prompted Simone to set up a website with her friends called Women in Refrigerators with a list of misogynistic depowerings, maimings and deaths of female comics characters. Simone had recognized that creative teams were trying to make death and torture more powerful in comics, not by telling more meaningful stories, but by crossing former dotted lines around female characters and children.

No One is Safe: Anyone and everyone can die. Titans #22 (Apr. 2010)

Another way to shake up the fans is to give them the feeling that no one in the fictional universe is safe. Heroes would normally have the benefit of metafictional immortality. But now they don't. Not even the most beloved characters are safe. Nor are the tough old villains who’ve been around for a dog’s age and until now, always escaped to fight another day. A recent illusion inflicted upon Starfire by the villainess Phobia sees her turn a corner in the Titans Tower, only to encounter a new wing in the team’s heroic hall of the dead – with all her 80s teammates in it (except the ones who are already dead, and are up in the first wing). To see how much the tone has changed in these books over the years, consider that in the 1980s, the Titans Tower used to feature a gallery of its living, current members – not a roster of its dead.

That was then. NTT #39 (Feb. 1984)

This is now. Titans #22 (Apr. 2010)

Like I say, villains aren't immune to this either. One of the Doom Patrol’s and Titans’ most steadfast enemies, The Brain, begged his genius gorilla assistant/love interest, Monsieur Mallah, to be allowed to die so that he could stop being an immortal brain in a jar.

The Brain: "Why won't you just let me die?" Outsiders #37 (Aug. 2006)

The Brain finally got his wish in the Salvation Run #4 (April 2008) tie-in to Final Crisis. In other words, Anyone Can Die, even tough old villains who have escaped death for many decades.

Anyone Can Die: Deaths of The Brain and Mallah. Salvation Run #4 (Apr. 2008)

Anyone Can Die includes taking a stab at younger characters with a younger fanbase, who are less used to having their fan-favourites tossed under the bus, as happened with the death of Superboy in Infinite Crisis #6 (May 2006).

Oh the humanity! Superboy is now alive and well again. Infinite Crisis #6 (May 2006)

But no over-the-top attempt to make death meaningful can conceal the fact that in pulp fictional worlds, death is not death. There are plenty of fourth wall practical reasons for this. Wiki quotes writer Geoff Johns as saying “Death in superhero comics is cyclical in its nature.” During the Modern Age, death in comics has become a ‘time out’ for the character whose popularity has declined, who has fallen out of favour with creative teams or editors, or who needs a new creative team and time for real world logistical factors to kick in. Johns also attributes killing characters off to “story … [and] copyright reasons.”

Peter Chung lays the blame at the feet of the “unhappy marriage” between comics and Hollywood. He says cross-pollination between film and comics generally degrades the complexity of the original pulp medium. Complex characterization has gone out the window, in favour of cheap tropes:

“Ironically, the wide dissemination of comics-derived films and TV. programs can be blamed for the decline in both the level of public interest in comics, and in the quality of the output of comics creators. That is, the success that comics enjoy by their acceptance in the more mainstream media of film and TV. is the very thing which is suppressing their artistic evolution.Beyond these practical concerns – which do have an enormous impact – the fact that death is not death in today’s heroic stories has moral implications. Above all, death has become a story-telling device to build up characterization, usually of characters surrounding the hero (or villain) who dies. Death in comics creates a belated Camus-esque existential crisis in the world of superheroes affected by it. Death doesn’t just provoke its characters to feel more intense emotions (because with fourth wall irony, even the characters themselves are cynical about repeated deaths and resurrections by now). Death also supposedly opens doors to new levels of characters' introspection.

When Hollywood adapts comic characters to the big screen, there is an emasculation effect whereby producers and directors, refusing to acknowledge serious themes present in the original work, exploit only the 'high-recognition/high concept' aspects for their own commercial ends. Comics are regarded as trafficking in stereotypes, and thus, as a source, provide an easy excuse for directors unequipped or unwilling to handle complex characterization. Mainstream audiences, seeing only the bastardized movie version of a comics character, have their preconceptions confirmed, thus inhibiting their desire to consider picking up a comic book to read.

Comics creators are only too eager to perpetuate this cycle by offering characters tailored with an obvious eye toward movie deals and merchandising licenses. These characters can be recognized by their flashier costumes, bigger muscles, bigger breasts, wider array of props, weapons, and vehicles, and most importantly, their pre-stripped down personalities (mostly consisting of a single facial expression), ready for easy portrayal by untalented athletes/models. Hardly a comic book character appears today without this aim in mind, and the trend is effectively dumbing down the readership.”

Read Rant blog remarks that: “There’s definitely an audience for stories that deconstruct super heroes. Comic book readers and creators alike have been obsessed with doing so at least since the publication of Alan Moore’s Watchmen.” Watchmen pondered the rise of Postmodernism in comics, the notion that there were no objective ideals. The problem is that superheroes originally embodied objective ideals. When those ideals were replaced with Postmodern subjectivity and moral relativism, then superheroes began confronting internal nihilistic atomization, which is what has lately been happening in one big crossover series after another. At first, Postmodernism dismantled universal values, but still preserved the integrity of the individual. There was no truth except what was true for each individual ('as long as it's true for you it's ok'). Watchmen followed that line. The famous graphic novel explored how people with radically different perspectives could always have a point, even if what they did was horrifying - like Rorschach. And if they were powerful enough like Veidt or Dr. Manhattan, they could see the biggest picture. Good would become evil - and evil would become good. The Watchmen tore down classic superheroic ideals, but it still worked because its individual characters remained powerfully intact. For example, although his methods were psychopathic, as an individual Rorschach stood on the line of objective values of good and evil and never wavered:

“Soon there will be war. Millions will burn. Millions will perish in sickness and misery. Why does one death matter against so many? Because there is good and there is evil, and evil must be punished. Even in the face of Armageddon I shall not compromise in this.”Rorschach repeats this later, and this maxim finally leads to his death, while his partner Nite-Owl characteristically does waver. They both stay true to who and what they are – and each has a defensible moral perspective. It's terrible, but by preserving the sanctity of the individual, Watchmen showed that moral relativism could work, albeit with chaotic and frightening results:

“Nite-Owl: Rorschach...? Rorschach, wait! Where are you going? This is too big to be hard-assed about! We have to compromise!But after the Watchmen, mass deaths in comics have involved the Postmodern deconstruction of the individual hero. This has strangely accelerated since 9/11. September 11 revived a faltering comics industry that has traditionally dealt with the core archetypes of society. One would have thought that the tragedy would inspire a revival of old school heroic ideals and true blue heroism. Instead, heroes and heroism have unravelled. Narrative has been removed. Character has been removed. The core principles, the symbolic values that heroes once embodied, have been demolished. Now those heroic ideals are being dismantled and replaced by a range of individuals' emotions and subjective perceptions, rendered into weapons or forces of power. But these are in turn broken up by introspective uncertainties.

Rorschach: No. Not even in the face of Armageddon. Never compromise.”

DC’s Infinite Crisis (2005-2006) dealt with the crumbling of heroic ideals like truth, justice and love. The crossover Final Crisis (2008) dealt with the aftermath of the collapse of heroic ideals, that is, with the ‘day evil won.’

DCU's Trinity grappling with the collapse of heroic ideals. Infinite Crisis #1 (Dec. 2005)

"Love is powerless" for the Titans, the DCU team that defends heroic emotional values. Infinite Crisis #1 (Dec. 2005)

In the 2000s, Postmodern treatments of superheroes went past the approach taken in Watchmen. The most recent stories deconstruct the individual hero or heroine – and relativize personal perceptions inside the hero’s own mind. Like the current treatment of Geo-Force on The Outsiders, the hero’s friends and teammates can no longer count on the hero as an individual. That’s because the hero can no longer trust himself. The idea is: 'Can you really trust yourself? No one knows what they will do if pushed to breaking point.' With Postmodernism, there's always a new mirror to break through, another metaphysical level at which you can doubt yourself, who and what you are, what you feel, and whether right or wrong can be pinned to any of that. That's Blackest Night, Cry for Justice, Rise of Arsenal – the values are gone, and any innate heroism stemming from an individual’s private life, or even his or her mind – is being stripped away. How deep will DC go? And what will they reveal when they go past all the boundaries of (super)human psychology?

The resurrected are 'back for a reason' according to Johns. Blackest Night #8 (Apr. 2010)

In Blackest Night and Brightest Day, mass death has been married to this breaking down of heroes’ internal subjectivities. Superficially, both series relate heroes’ emotions in the face of death to DC’s now-multi-coloured Lantern universe. By these means, emotions are now weapons in the DCU. But beneath this probing of subjective emotion, Geoff Johns is installing another sub-basement in the heroic sub-conscious. What new heroic standards, based on shattered egos and fractured ids, are emerging? What heroic standards will appear when everything that traditionally gave heroic stories their form and content – narrative, character, objective values, subjective perceptions and experience, and individual integrity – are all gone?

Comic Book Death has become a symbolic tool for dismantling the heroic ego. In this context, the opposite of death is not immortality. The opposite of Comic Book Death is the collection of impermeable, objective values that superheroes represented in the Golden and Silver Ages. Comic Book Death also opposes the whole Postmodern concept that an individual can be heroic on his or her own terms. Thus, mass death opens up doors to a new pantheon of superheroic archetypes that have not yet been defined, but will be once the individual is crushed - presumably by one resurrection too many. Welcome to the terra incognita of Post-Postmodern values.

Go Back to Reflections on the Revolving Door of Death 1: Titanic Legacies for Generation X Superheroes.

Read all my posts on the Revolving Door of Death.

Read all my posts on comics.

All DC and Marvel Comics stories, characters and the distinctive likenesses thereof are respectively Trademarks & Copyright © DC and Marvel. Aeon Flux © MTV. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

God, so many death tropes...

ReplyDeleteI'm actually kind of afraid of "Mummies at the dinner table". And thanx again for mentioning the list.

(Oh, and the Lian Harper group has a sister group on DeviantArt. Currently 102 members and 111 watchers)

Thanks for your comments! I'm glad someone counted all those dead characters. I think it's a milestone in comics history.

ReplyDeleteWhat's the link to the DeviantArt group? I can incorporate it into the post.

Here you go:

ReplyDeletehttp://bringbacklianharper.deviantart.com/

That COIE image is originally derived from the Pietà. It is an image of Mary holding the dead Jesus, and is a common trope in Christian art. The most famous is Michelangelo's, which you can find here:

ReplyDeleteCoincidentally, he came back from the dead, too.

Don't know why I didn't catch that! I think maybe seeing Homer Simpson in the place of Mary somehow prevented my seeing it. Thanks very much for the comment D.W., I've signed up to follow your very interesting looking blogs.

ReplyDelete